I like solving problems from TopCoder competitions for fun. The site offers a variety of language options, including C++, C#, Java, and Python.

The Problem

One problem in SRM 295 called BuildBridge (2nd problem on that page) highlighted an issue that often comes up in discussions of Python: Performance. In short, it asks how many cards of width L have to be stacked on top of one another to create a bridge that can span width D. To get the full text of the problem definition, you’ll need to log into TopCoder.

The important thing to note is that for some of the allowed inputs, a simple loop has to run about 36.8 million times. The loop contains a multiplication, a division, a comparison, and a few additions.

Here’s one solution written in Python

class BuildBridge:

def howManyCards(self, D, L):

cards = 0

hang = 0.0

denom = 0.0

while (hang < D):

denom += 2

hang += (1 / denom) * L

cards += 1

return cards

TopCoder gives you bounds on the input possibilities and a certain amount of time for your code to run on their test servers. If you pass each test case in time, your solution is accepted.

The longest run time you’ll get is with D = 9 and L = 1. It turns out this solution (which is also included as a test-case) is 36,865,412 cards.

My tests were all passing and I was confident in the correctness of the solution, but I was failing TopCoders tests (specifically the one case above) because the execution time was too long.

On my own computer, running Python 2.7, the slowest case was taking a whopping 8.41 seconds! Of course TopCoder problems are meant to be solved quickly (in terms of coding time), and not necessarily in the most efficient possible way. Was there some way to optimize this code?

Of course: Here’s some more optimal code that factors out an unnecessary multiplication:

class BuildBridge:

def howManyCards(self, D, L):

cards = 0

hang = 0.0

x = 2.0 * D / L

while (hang - x < 0):

cards += 1

hang += (1.0 / cards)

return cards

Now we’re avoiding a multiplication. Hooray. Yet we’re STILL failing the tests. How long does this code take? 6.81 seconds. Still not even close to the 2 second limit we’re dealing with.

Fortunately, TopCoder lets you look at other people’s solutions (for these archived SRM problems that have already been used in competitions). The top-scoring Python submission used this little trick:

...

if D == 9 and L == 1:

return 36865412

...

D and L are guaranteed to always be integers, and D of 8 will complete in the alloted (since it only has to loop about 5 million times). This technically works, but as Raymond Hettinger likes to remind us, “There MUST be a better way!”.

Python vs. ____

My curiosity got the better of me, and I had to see how Python stacked up against other languages. I first ported my (unoptimized) solution to C++:

class BuildBridge {

public:

int howManyCards(int D, int L) {

int cards = 0;

double hang = 0.0;

double denom = 0.0;

while (hang < D) {

denom += 2;

hang += (1 / denom) * L;

cards += 1;

}

return cards;

}

then C# and Java (which look pretty much identical to the C++ version above, and then a few other languages (Ruby, JavaScript, and Go).

To give Python a fair chance, I also tried a few implementations other than the de facto standard CPython: PyPy, IronPython, Jython, and Cython. The code remained unchanged except for Cython, which allows static type declarations in its .pyx format:

...

def howManyCards(self, int D, int L):

cdef int cards = 0

cdef double hang = 0.0

cdef double denom = 0.0

...

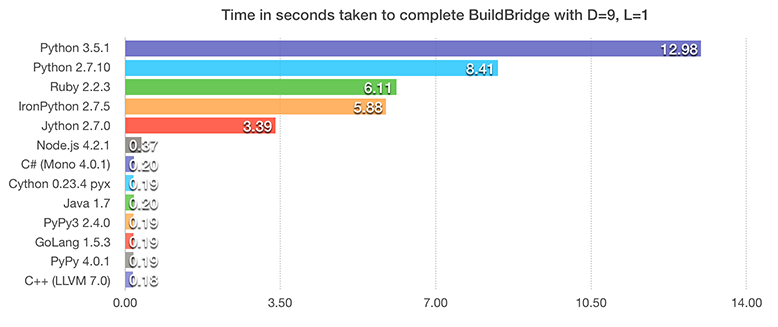

Here are the results:

Unsurprisingly, the interpreted languages are slower. Surprisingly, our example takes considerably longer under CPython Python 3.5 than it does in the 2.7 interpreter. It took 65 TIMES longer than our compiled languages and about 55% longer than CPython 2.7.

IronPython and Jython are really meant more for interoperability of code, so we can’t blame them too much for also being quite slow. The Jython implementation took 17 times longer than the pure Java version.

Interestingly, Cython (with its type annotations) didn’t give us much of a boost over PyPy. The impressive performance from PyPy, C#, and Java demonstrate the power of JIT compilation.

What’s going on in there?

For a lark, I ran the unoptimized solution through a Python line profiler to see if any particular line was tripping up CPython.

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

==============================================================

2 @profile

3 def howManyCards(self, D, L):

4 1 3 3.0 0.0 cards = 0

5 1 1 1.0 0.0 hang = 0.0

6 1 0 0.0 0.0 denom = 0.0

7 36865413 16790669 0.5 23.7 while (hang < D):

8 36865412 16984466 0.5 24.0 denom += 2

9 36865412 20937285 0.6 29.6 hang += (1 / denom) * L

10 36865412 16011337 0.4 22.6 cards += 1

11 1 1 1.0 0.0 return cards

We can see the line with the multiplication and division taking a bit longer than the others, but nothing really stands out here. For more on what exactly CPython is doing, check out Why Python is Slow by Jake VanderPlas.

So why use CPython over PyPy?

If you want Python 3.5, your only option is CPython. While PyPy3 does support 3.2.5, it is based on an older version of PyPy and can occasionally be much slower.

If you’re running a web app or service through something like Django, Flask or Bottle, PyPy is great. It even supports greenlets. There are, however, compatibility issues with some tools. If you want to use NumPy, for example, you’ll need to use the PyPy compatible fork. There are also a few other differences.

I ended up creating a few virtual environments on my development machine (using virtualenvwrapper). This makes it easy to switch between different implementations depending on your needs.

Some of the cool new Python features you can’t yet use with PyPy include PEP 448. I recently learned about this in a great article about ‘Pythonicness’ and readability by Trey Hunner. If you look at the performance comparison linked from that article, you’ll see that using the ** dictionary unpacking operator is actually the fastest method of the ones listed.

Many features, like the enum module, have been back-ported to previous versions of Python. A quick pip install was the only change required to get a personal project I’ve been working on running with PyPy3.

Not a very useful benchmark

Real-world programs rarely consist only of loops of simple arithmetic with no data structures or I/O and tens of millions of iterations. Our TopCoder example has CPython (2.7) running about 40 times slower than PyPy, but PyPy’s own benchmarks (which use a variety of more realistic use-cases) show CPython to be “only” about 9 times slower.

In many cases, performant external libraries written with C (like SciPy or NumPy) are doing the heavy lifting.

The Takeaway

- CPython is an interpreter not primarily concerned with performance.

- Python is not inherently slow, at least not significantly more than C# or Java.

- If you are writing pure Python and care about its performance, use PyPy (or maybe Cython).

- If you’re on TopCoder and you think the solution may require a lot of computation, consider using a different language (or at least be aware of potential pitfalls).